The end of the market

Markets are an incredible way to organize and share the spoils of labor, but in many aspects they are based on assumptions that no longer hold true. A dive into how the open source economy radically changes how we trade.

As you know, markets are where people trade things with one another. They allow people to specialize, leading to economies of scale and super-duper efficient theoretical production. As a practical example: If I had to dig out iron ore by hand to make steel, I couldn’t build a bicycle in a month, but if I work on something I’m good at for a month, then I can go to a market and buy one with just one months “work” as payment. That is economies of scale at work, and the market is what makes it possible.

In a theoretically perfect market, we could, somewhat simplified, say that each person puts in labor, and gets back the equivalent of that labour times the average economies of scale of that market. If the economies of scale of a market mean things on average get produced in 1/500th the time it would take if you made everything yourself, then that means you get 500 times the work you put into the market back out of it.

This is all fine and dandy. The problem is that we settle here. We look at this and we say “holy crap, that’s awesome, markets are so cool, lets all go buy the new iPad!”. And when we do that, we miss some very important (flawed) assumptions we make about why and when markets are useful.

For one, we assume that when we consume a resource that we have produced, that resource is consumed.

Consumptionless consumption

When I eat an apple someone has grown, its gone. No more apple. When I buy a used car and use it until it breaks down, it’s gone. This is a key part of the rationale behind having a market.

Let me try and illustrate this. A good example of an early market is what happened 14 000 years ago when the first farmer produced a bit too much wheat and traded the excess for an embroidered hog pelt. Why didn’t she just give the excess away? Because (and this sounds ridiculously obvious, but bear with me) if she gives some wheat away, she can’t keep it. So she asks for something in return, to make up the lost wheat.

But what if she could give away the wheat, and still keep it?

Then it would not make sense to trade. That first pile of wheat produced by that first farmer would have been it. She would have made a pile that we all could “consume” indefinitely.

As you’ve guessed by now, there are some resources that do work like this. “Consuming” the Linux operating system does not take it away form someone else. Music and writing works the same way. The cost of you reading this is so infinitely small for me, that I can let everyone do it for free. Software, writing, music – any “information”-based product, really – these are, for lack of a better word, additive resources, and markets don’t make sense for many of them.

A ‘market’ of additive resources does not work the way a market as described above does. Rather than multiplying your labor, an additive market gives you back everything anyone has ever put into it, and putting labor into it yourself is optional.

When you think about it, many of the resources we use are additive. Some are not, like wheat and cars. Knowledge of how to grow wheat or how to create raw material for a bicycle however,those are additive resources. What is really interesting is that knowledge of how to make machines that grow wheat is also additive.

With open source fabrication projects like RepRap, the free 3d printer, evolving alongside open source designs of everything from fashion accessories to wind mills, something really interesting is happening. We are effectively using additive resources to bring down the cost of classic resources. Designs for machines that make basic raw materials out of common natural resources, printable with a 3d-printer using those very same materials, are not unreasonable to imagine.

</p>

</p>

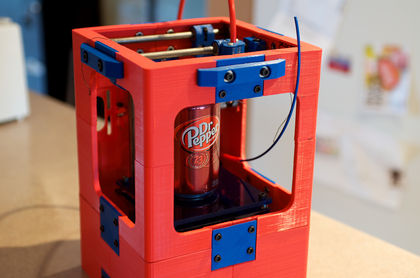

This RepRap variation is a 3d printer, printed by another 3d printer from open source blueprints that anyone can improve on.

There is a revolution brewing, aimed at making physical things cheap enough to produce that the additive aspects of them become the primary aspects, and it is set to replace the economists favorite pet.

There are lots of interesting tangents here, like when additive resources still work better in classic markets (hint: When the barriers of entry are high), or how general purpose production trumps economies of scale. It would also be super cool to imagine useful raw materials, and look at what barriers keep local fabrication back.. Probably a ton of other things as well. Lots of blog posts to write, so little time..